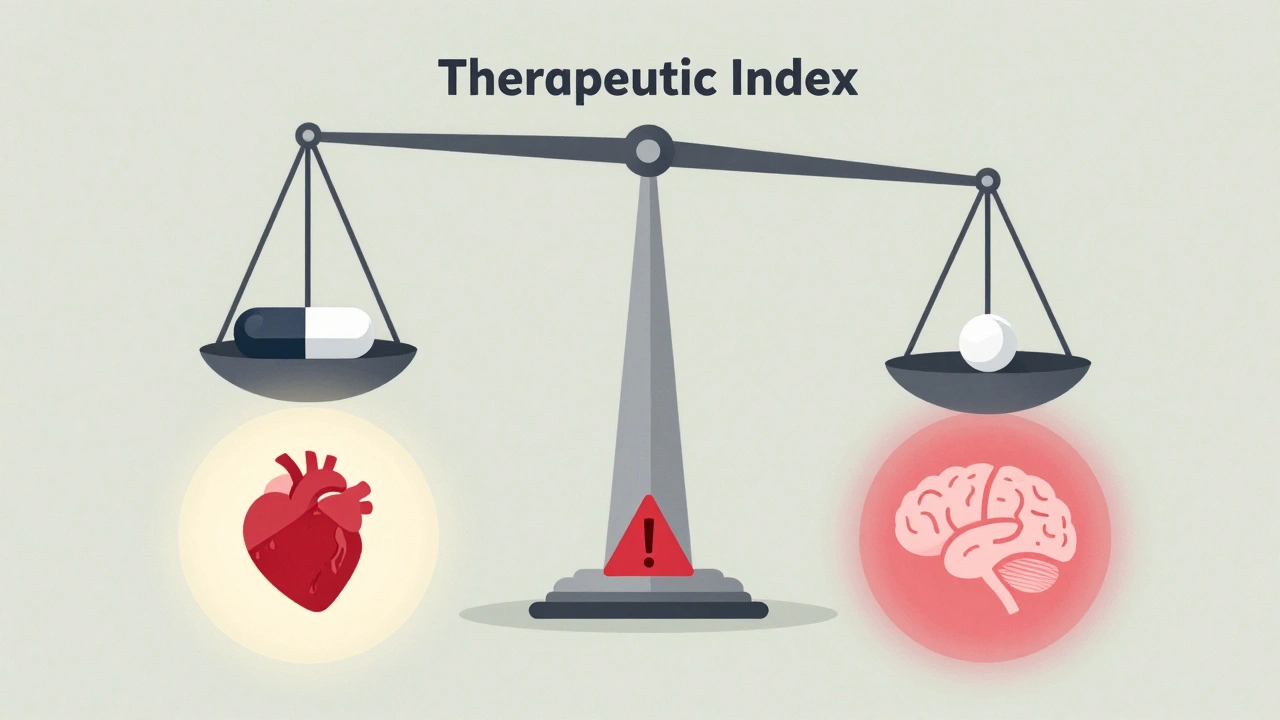

Some medications leave no room for error. A tiny change in dose - even 5% - can mean the difference between healing and hospitalization. These are narrow therapeutic index drugs (NTI drugs), and they demand far stricter rules when generic versions are made. Unlike most generics, which can vary by up to 25% in how much drug reaches your bloodstream, NTI drugs must match the brand-name version almost exactly. Why? Because the line between effective and dangerous is razor-thin.

What Makes a Drug a Narrow Therapeutic Index Drug?

A narrow therapeutic index means the gap between a helpful dose and a toxic one is very small. The FDA uses a cutoff of 3 or less for the therapeutic index - that’s the ratio of the toxic dose to the effective dose. If a drug’s index is 2.5, it means you’re only 2.5 times away from an overdose when you take the right amount. That’s not a lot of wiggle room.

These aren’t obscure drugs. They’re critical, life-saving medications used daily by hundreds of thousands of people. Think digoxin for heart failure, levothyroxine for hypothyroidism, warfarin for blood clots, phenytoin for seizures, and tacrolimus for transplant patients. Take too little, and the condition returns. Take too much, and you risk organ damage, bleeding, or even death.

Doctors have known this since the 1970s, when therapeutic drug monitoring became common. Blood tests were needed to make sure levels stayed in the safe zone. But even with monitoring, small differences between brand and generic versions could cause problems. That’s why regulators had to step in.

How Bioequivalence Rules Changed for NTI Drugs

For most generic drugs, bioequivalence is measured by comparing how much of the drug enters your bloodstream - measured as AUC (area under the curve) and Cmax (peak concentration). The standard rule? The generic must deliver 80% to 125% of the brand’s levels. That’s a 45% range. It works fine for most medications.

But for NTI drugs, that range is too wide. A 125% exposure could push a patient into toxicity. A 80% exposure could let their condition flare up. So regulators tightened the rules.

The FDA now requires three things for NTI generics:

- Reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE): The acceptable range adjusts based on how variable the brand drug is in people. If the brand varies a lot between patients, the generic can vary a bit more too - but only up to a point.

- Variability comparison: The generic must not be more variable than the brand. If the brand stays consistent from dose to dose, the generic must match that consistency. This is checked using a statistical test that compares within-subject variability.

- Unscaled average bioequivalence: Even with scaling, the generic still has to fall within the traditional 80-125% range. This acts as a safety net.

Health Canada uses a fixed range of 90.0-112.0% for AUC. The EMA uses 90-111% for both AUC and Cmax. These are tighter than the standard 80-125%, but they don’t adjust based on variability like the FDA’s method. The FDA’s approach is more complex, but also more precise - it lets in generics that are just as reliable as the brand, while keeping out those that are too inconsistent.

Why This Matters for Patients

Imagine you’ve been on brand-name warfarin for years. Your INR levels are stable. You switch to a generic. Suddenly, your blood starts clotting too easily - or worse, you bleed internally. That’s not hypothetical. Before stricter rules, there were real cases where patients had to be rehospitalized after switching to a generic NTI drug.

But here’s the flip side: many patients have switched safely. A 2019 study in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes found no difference in stroke or bleeding rates between brand and generic warfarin when the generic met the new bioequivalence standards. A 2017 study in the American Journal of Transplantation showed that generic tacrolimus performed just as well as the brand in kidney transplant patients - as long as the generic passed the FDA’s strict criteria.

So the rules aren’t about stopping generics. They’re about making sure only the safest, most consistent generics get approved. That’s why the FDA doesn’t just look at average levels - it looks at how much the drug swings from one dose to the next in the same person. Consistency matters as much as potency.

Who Makes These Drugs - and Why It’s Hard

Developing a generic NTI drug isn’t like making a generic painkiller. It’s expensive. Studies now require 36 to 54 volunteers, compared to 24 to 36 for regular generics. The trials are longer, more complex, and often use a fully replicated crossover design - meaning each patient takes both the brand and the generic multiple times, in different orders, over weeks.

That drives up costs. A standard bioequivalence study runs $300,000 to $700,000. For an NTI drug? $500,000 to $1 million. That’s a big barrier for smaller manufacturers. As a result, only a few companies make generics for drugs like levothyroxine or tacrolimus. That limits competition - and sometimes keeps prices higher than they should be.

Some experts worry the rules are too strict. Dr. Lawrence Lesko from the University of Florida has argued that for some NTI drugs with very low variability, the extra requirements don’t add safety - they just add cost. But others, like Dr. Leslie Benet from UCSF, say the FDA’s approach is scientifically sound. It’s not about being harsh - it’s about being smart. If a drug can kill you if it’s off by 10%, then you need better proof it’s safe.

The Biggest NTI Drugs You Might Be Taking

Here are the most common NTI drugs recognized by the FDA, EMA, and Health Canada:

- Levothyroxine (for thyroid disease)

- Warfarin (blood thinner)

- Phenytoin (seizure control)

- Digoxin (heart rhythm)

- Tacrolimus and Sirolimus (organ transplant rejection prevention)

- Carbamazepine (seizures, nerve pain)

- Lithium carbonate (bipolar disorder)

- Theophylline (asthma, COPD)

- Valproic acid (seizures, mood stabilization)

The FDA doesn’t publish a full official list - it issues guidance case by case. As of 2023, they’ve published specific bioequivalence guidance for 15 NTI drugs. That creates uncertainty for manufacturers trying to develop new generics. If you’re not sure whether your drug is classified as NTI, check the FDA’s website for product-specific guidance documents.

Why Generic NTI Drugs Still Have Low Market Share

Even with safer generics available, adoption is slow. In 2021, a study in JAMA Internal Medicine found that only 68% of NTI drug prescriptions were filled with generics - compared to 90% for other drugs. Why?

Doctors are cautious. Patients are nervous. Pharmacists sometimes can’t substitute without prescriber approval. Even if the science says it’s safe, trust takes time to build. But the data is growing. Real-world evidence from transplant centers, cardiology clinics, and epilepsy programs now supports generic NTI drugs - as long as they meet the new standards.

That’s why the FDA is working on a more systematic way to classify NTI drugs. Right now, it’s done case by case. Soon, they plan to use quantitative calculations of therapeutic index - not just expert opinion - to decide which drugs need stricter rules. This could make the process fairer and faster.

What’s Next for NTI Drug Regulation?

The FDA plans to issue final guidance on its RSABE approach by mid-2024. That will make the rules official, not just draft. Meanwhile, regulators in Europe and Canada are watching closely. There’s talk of harmonizing standards by 2026. If the U.S., EU, and Canada align on one set of rules, manufacturers won’t have to run three different studies. That could cut development costs by 15-20%, according to McKinsey & Company.

That’s good news. Because while the rules are strict, they’re necessary. These drugs save lives - but only if they’re consistent. The goal isn’t to block generics. It’s to make sure every pill, every dose, every bottle is as safe as the brand. And that’s something every patient deserves.

joanne humphreys

7 December 2025 - 07:12 AM

It's fascinating how much precision goes into something most people assume is just a cheaper version of the same pill. I never realized that consistency in absorption matters as much as potency for drugs like warfarin or levothyroxine. This level of regulatory nuance is what keeps people alive.

Chris Park

8 December 2025 - 00:44 AM

Let’s be real-this whole ‘narrow therapeutic index’ framework is a corporate shield. The FDA doesn’t want generics competing because Big Pharma pays them to keep the playing field tilted. They invented ‘RSABE’ to confuse everyone into thinking it’s science when it’s just legal obfuscation. Look at the cost: $1M per study? That’s not safety-it’s a tax on competition. And don’t get me started on how they ‘case-by-case’ classify drugs. It’s arbitrary. It’s corrupt. And it’s why your insulin still costs $300.

Priya Ranjan

9 December 2025 - 11:09 AM

Anyone who takes a generic NTI drug without consulting their doctor first is playing Russian roulette with their life. I’ve seen patients crash after switching-thyroid levels off by 0.3, INR through the roof. It’s not ‘trust’ that’s the issue-it’s ignorance. People think ‘generic’ means ‘same.’ It doesn’t. Not for these drugs. And if you’re the type to save $10 on your levothyroxine, you’re not frugal-you’re reckless.

Dan Cole

9 December 2025 - 11:45 AM

There’s a philosophical abyss here: if a drug’s safety hinges on milligram precision, then we are not treating disease-we are engineering human biology like a clock. We’ve outsourced our physiological stability to a chemical formula, and now we demand perfection from a pill. But pills are not perfect. People are not perfect. And yet we demand that the system be flawless. Isn’t that the ultimate hubris? We fear variability in medicine, but we ignore the variability in human experience-the stress, the diet, the sleep, the gut flora-all of which alter drug metabolism more than any generic formulation ever could. The real issue isn’t bioequivalence-it’s our delusion that medicine can be standardized into safety.

Nigel ntini

9 December 2025 - 22:35 PM

Big props to the FDA for not cutting corners here. I know it’s expensive and slow, but imagine being the transplant patient whose body rejects the new organ because the tacrolimus dose drifted. This isn’t about profit-it’s about dignity. People deserve to know that the pill they take today will behave the same tomorrow. That’s not luxury. That’s basic care.

Ashish Vazirani

10 December 2025 - 01:08 AM

This is why America is falling apart!!! The FDA is letting foreign labs make our life-saving drugs!!! Who knows what’s in those pills?!!! I heard China controls 80% of the API supply!!! And now they want to make generics even cheaper??? This is a national security threat!!! People are dying because of this!!! Someone needs to burn down the FDA!!!

Max Manoles

11 December 2025 - 06:15 AM

I’ve worked in a hospital pharmacy for 12 years. We switched our entire cardiac unit to generic warfarin after the new standards came in. Zero adverse events in 3 years. The key? Stick to one generic brand. Don’t switch between them. Consistency in manufacturer matters as much as regulatory approval. The science is solid-what’s broken is the system that lets pharmacists swap brands without telling the prescriber.

Katie O'Connell

12 December 2025 - 07:55 AM

It is, in fact, a matter of considerable scholarly interest that the regulatory framework governing narrow therapeutic index pharmaceuticals exhibits a marked divergence across jurisdictions, particularly in the application of reference-scaled average bioequivalence versus fixed limits. The EMA’s approach, while statistically less adaptive, possesses a certain epistemological elegance in its simplicity. The FDA’s model, though more rigorous, introduces an element of algorithmic opacity that may undermine clinical confidence. One might posit that the current paradigm reflects a technocratic overreach, wherein statistical modeling supplants clinical intuition-a trend that, if unchecked, may erode the physician-patient alliance.

Ibrahim Yakubu

12 December 2025 - 20:41 PM

Chris Park’s comment about corporate control? He’s not wrong. But let’s not pretend the FDA is the villain. The real problem? Patients don’t know their own meds. I’ve seen people take two different generics of levothyroxine in one month and then blame the doctor when they feel tired. It’s not the drug-it’s the lack of education. The FDA did their job. Now we need to educate the public. Or we’ll keep having this same debate in 2030.